Deadly buildings

Architecture and indoor air, a blind spot of the Covid-19 pandemic. Health risks in places of social interaction.

This text is a transcript of a presentation made at a conference organized by Winslow Santé Publique in September 2024 at the Condorcet campus of the School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS): « From Pandemic Demobilization to Covid Activism — Science, prevention and mobilization in the face of the pandemic »

Thank you to Robert and Annette @annetteb.bsky.social for the help on the translation.

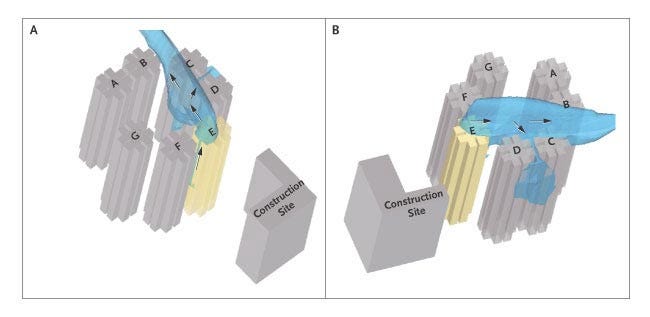

My first specific alert about SARS-CoV-2 came in January 2020 through SARS-CoV-1, with an article I read alongside questions about the new coronavirus. Published in April 2004 in the New England Journal of Medecine under the title « Evidence of Airborne Transmission of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Virus », it documented a cluster of contaminations during the SARS epidemic at the Amoy Garden, a group of high-rise apartment buildings in Hong Kong. I was struck by the diagrams of the virus-laden aerosol plume carried by the wind among apartments at nearby levels but in different buildings.

At the time I was in Canada with my family, and I quickly asked myself how air was redistributed throughout the buildings, including the one that we lived in, by HVAC systems (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) which are very common in North America. These thoughts led me to buy our first N95 respirator masks, suited to filter out aerosols, rather than less effective simple surgical masks.

We would find out soon enough that, like SARS-CoV-1, the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for Covid-19, is almost exclusively airborne. It flows from the exhalation of someone who is contagious to the inhalation of a healthy person via infectious aerosols which, without adequate ventilation, filtration or disinfection, remain lingering in the air.

Let’s take another look at the astonishing conversation that the three co-authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, all of them epidemiologists and public health specialists1 held with journalists in the fall of 2020. The premise of the declaration is that the lifecycle of an epidemic caused by a novel virus in a naive population, where immunity is achieved via infection, doesn’t exceed three to four years. They were thinking of measles, where the ensuing immunity lasts a lifetime).. In their understanding, the sooner the population achieves immunity by exposure to infection, the sooner we will be able to return to a normal life. Even without training in epidemiology, virology or medicine, one can see that this acceptance of the celebrated herd immunity theory, on which the majority of the world’s countries had based their healthcare response by the summer of 2020, is hazardous as well as unethical (to say the least) when it comes to an emerging virus. Not only did other aspects of the declaration raise serious ethical questions and anchor its ideology in modern-day eugenics, it quickly became apparent that immunity to SARS-CoV-2 upon infection only lasted a few months, giving rise to the probability of multiple infections, of the emergence of new variants, of cumulative risk of immune system damage and of damage tied to viral neurovascular persistence. The last five years have, unfortunately, confirmed that this approach was a disastrous mistake.

Because I am convinced that the best way to fight infections is by preventing them, and perhaps also because I am an architect by training, I set out to look at transmission where airborne viral particles in a closed environment can hang in suspension for several hours after they have been exhaled, even if a contagious person is no longer present. I put myself upstream of contamination, something the authors of the GBD never thought of. Indeed, they never gave any consideration to the possibility of avoiding viral transmission, or of at least reducing the number of occurrences. And, unless the intention of the GBD was to deliberately infect the greatest number of people as fast as possible, this is a fundamental unthinkable.

We’re now in May 2025, and I remain dumbfounded that these considerations have remained unaddressed for such a long time, and that the responsibility for formulating public policy responses to Covid-19 has been totally relinquished to the medical profession.

If the dramatic example of the spread of the virus at the Amoy Garden is significant, averting the concentration of infectious aerosols should almost completely eliminate the risk of contamination. This is far more effective than relying on herd immunity when it comes to an unknown virus. And beyond that, it is effective for all the airborne pathogens listed below.

Outdoors, speaking of the contagiousness of SARS-CoV-2, the risk is therefore slight, almost nonexistent if one is not directly in someone else’s exhalation plume. Dilution by the outside air, which is in continual motion, does the trick. The problem is the air we breathe indoors, where this natural dilution does not occur, where exhaled air accumulates and, with it, contagious aerosols.

In short, we have to be able to breathe air that someone else has not just exhaled.

The problem is compounded by the fact that most of our social interactions, and thus the opportunities for contamination, take place indoors. According to data from the U.S., almost 90% of our time is spent in closed buildings. A third of that is not in our own homes, but in offices, stores, schools, hospitals, restaurants, movie theaters, etc., to which we must add 6% in public transportation.

The problem has been made even worse since the mid-20th century because of the evolution of architecture that is more and more weatherproof, with closed and sealed buildings that require mechanical air management systems. The evolution of construction techniques combined with oil shocks and energy costs have pushed us to insulate in order to more easily regulate indoor temperatures. This is a point where climate change and epidemics converge, based on the fact that the rise in summer temperatures makes for longer periods when people protect themselves from outdoor heat by confining themselves as hermetically as possible, in winter against the cold, in summer against the heat.

The situation is further exacerbated by cultural changes and medical practices that have paradoxically dampened our natural reflexes to breathe fresh or refreshed air, wherever we are, and especially in healthcare facilities.

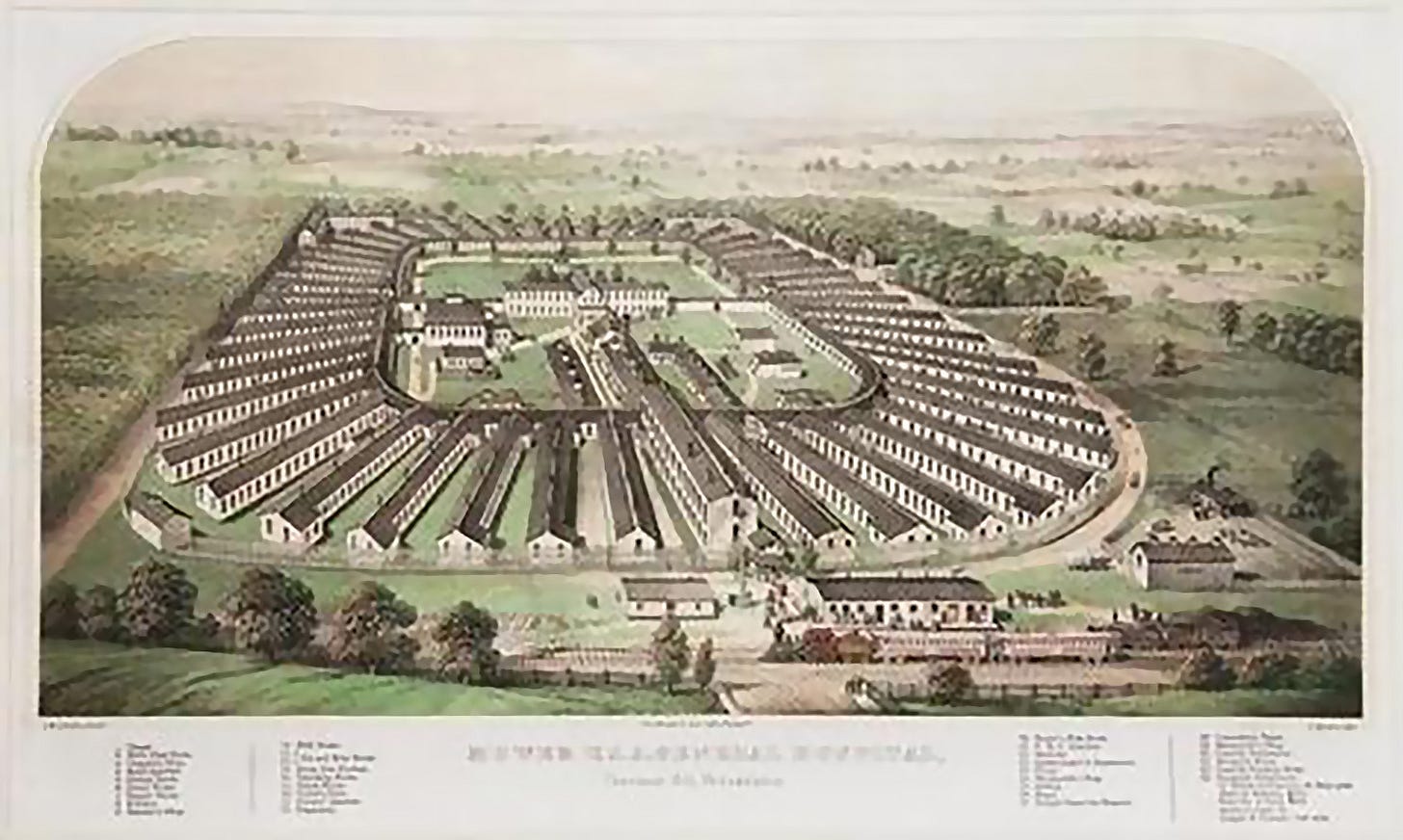

For example, the principle of windowless rooms suddenly appeared as a hospital « innovation » in the 1940s. In the two preceding centuries, hospitals were constructed based on the premise that natural light and fresh air are beneficial. Up until the beginning of the 20th century, the purpose of a hospital was to provide medium- to long-term stays with a greater level of hygiene than the patient would experience at home.

Then advances in medicine tilted the hospital towards becoming a technological service center, which required an organization and a kind of architecture that was more “efficient” and rational than the architecture that allowed for light and outdoor air to be brought in throughout the building. Hospitals became huge urban machines, among the most complex, incorporating other machines, their networks and their operators, with a rapidly changing population of patients at the center.

As the urbanist Paul Virilio2 might have put it, inventing a form of architecture severed from the exterior came with undeniable progress, but at the same time invented the accident of a disease-laden interior air.

We now live in sealed buildings. And sealed buildings are where most of our social interactions take place. The gamble might not have been lost if we had thought about managing indoor air, compensating for modern-day separation from the outdoors. But we didn’t do that. And contemporary architecture, where insulation from the outside has been perfected to a fault, now presents three different scenarios:

Structures without any air distribution system, where we breathe… whatever we find there, possibly improved by a window which is opened occasionally — if there IS a window, and if it can be opened — or by people’s comings and goings. It’s random and potentially catastrophic.

Structures where the air distribution system insufficiently renew the indoor air, or where the air distribution system is inoperative due to errors of design, maintenance or servicing. On this point, I’m borrowing the words of Jesse Smith, a specialist in energy renovation of buildings in the U.S., in a publication appearing in February 2024, where he made the following observation: « The importance of indoor air quality is no longer overlooked. Improving indoor air quality through interventions like adequate ventilation, proper filtration, and ultraviolet germicidal irradiation in public buildings could conceivably cut the transmission of respiratory illness by up to two thirds. But there are bottlenecks to the mass deployment of these new technologies. A 1Day Sooner/Rethink Priorities report lists three: a lack of clear standards, the cost of implementation, and difficulty changing regulation and public attitudes. I’d like to add a fourth: the workforce that will be tasked with installing them. » He next describes the dramatically low level of reliability and functionality of HVAC systems in the U.S.

Finally, in a very small number of cases, structures where the air distribution system is of an appropriate size and well enough maintained to assure continuous and satisfactory renewal of the air, as indicated by a CO2 concentration level below 500 or 600 ppm.

Some of us have learned, through the pandemic, of the existence of CO2 monitors - small, stand-alone devices which make real-time measurements of the level of CO2 in a volume of air, allowing for comparison with the ambient outdoor level, which in 2024 was around 410 ppm3. This difference indicates the amount of CO2 from the air exhaled by those who are present or have just left. In practice, the indoor level of CO2, which is the concentration of air exhaled, can shoot up at breathtaking speed depending on the space and the number of people in it. I have, for example, observed a sudden increase in a vehicle with four passengers, where the ventilation was set to recycle-only, which made the CO2 level jump to over 8,000 ppm in a matter of minutes.

Each new increment of 400 ppm of CO2 above the exterior level adds 1% to the portion of inhaled air coming from someone else’s exhalation. At 500 ppm of CO2 indoors, meaning very close to outdoor levels, this level of “respiratory recycling” is therefore 0.25%. At 2,400 ppm of CO2, which we see all the time in classrooms, waiting rooms, and doctors’ and dentists’ offices, 5% is recycled air. It reaches 10% once we reach 4,000 ppm of CO2, a level that is regularly seen in environments that are bustling with activity or have insufficient ventilation. And it rises to 20% recycled respiration in my example of a vehicle at 8,000 ppm of CO2, which is probably the same as what would be measured in crowded public transportation, for example.

As we move beyond the outdoor level, with human respiration raising the concentration of CO2 beyond 800 or 1,000 ppm, if some of this exhaled air is infectious, and there are no other preventive measures, contamination becomes more and more likely, not to say certain.

The level of CO2 is therefore a good indicator of the risk of infection in the indoor air we breathe.

All of which paints a bleak picture of a contemporary architecture inadequate to guarantee that one will leave a closed space after a few minutes or a few hours with the same health outlook, in the short term or the long term, as one had upon entering. This means that Covid-19 is an epidemic “of buildings” poorly adapted to the health of the individual, and that architecture is a key factor in controlling epidemics caused by respiratory transmission. This concept preceded the advent of SARS-CoV-2, but the violent development of the Covid-19 epidemic should have once again reminded us of these issues.

Joseph Allen, who leads the Healthy Buildings program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, sounded the alert in an article published March 4, 2020 in the New York Times. On the same day, in France, the entire population was about to be mixed together willy-nilly in polling places with questionable, possibly nonexistent, ventilation. Joseph Allen wrote: “Your building can make you sick or keep you well. Proper ventilation, filtration and humidity reduce the spread of pathogens like the new coronavirus.” He continues in the context of the first, brutal wave of Covid: “Bringing in more outdoor air in buildings with heating and ventilation systems (or opening windows in buildings that don’t) helps dilute airborne contaminants, making infection less likely. For years, we have been doing the opposite: sealing our windows shut and recirculating air. The result are schools and office buildings that are chronically underventilated. This not only gives a boost to disease transmission, including common scourges like the norovirus or the common flu, but also significantly impairs cognitive function.”

And indeed, some people who were well informed about the risks of enclosed spaces, particularly in the midst of the first deadly wave of SARS-CoV-2, quickly adopted recommendations and measures to improve the air inside their buildings and to enhance the safety of their employees. We have the example of the United Nations headquarters in Geneva, which, in its “Back to the Office (BTO) Plan” published on May 1, 2020, explained: “To ensure optimal ventilation within the areas with automatic ventilation systems, all systems have been switched to “100% fresh air circulation only”. The speed of the ventilation systems is also being increased two hours prior to the start of the working day and switched back to a lower speed two hours after the end of the working day. […] All filters for outside air have been replaced and maintenance of filters is strictly monitored.” This decision shows responsibility and common sense, but is quite cynical when you consider that on March 28, only a month earlier, the WHO had issued what was probably the most lethal message in public health history, stating categorically, « FACT: COVID19 is NOT airborne ». Five years later, we’re still struggling to get an official denial of this criminal disinformation, and recommendations which are tailored to reality.

There are rare initiatives promoting prevention, but the view prevailing in March 2020 persists. I would have liked to share Joseph Allen’s enthusiasm and the hope embodied in the name Healthy Buildings, but the architecture which forms our social spaces, which forms the solid, concrete framework, still gives rise to respiratory contamination in general and Covid-19 in particular. The violent epidemic of “flu-like syndromes” in the winter of 2024-2025, that affected even very young children and caused a health emergency that turned French hospitals into deteriorated operations — with cancellations, postponement of treatments, overworked caregivers — did not take place in a vacuum. All of this was as predictable as every flu epidemic before it.

As we don't know in advance what we're going to breathe and with what sanitary baggage we're going to emerge from any visit to an enclosed space, we can currently put forward the notion of Deadly Buildings.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2, or any other respiratory virus, is paradoxically quite easy but as of now unattainable. Essentially, we have to breathe air that is free of pathogens, meaning air that is sufficiently diluted (or filtered / disinfected) after its exhalation from a contagious individual. This sounds easy. In fact, it’s a lot easier to undertake than the gigantic work of creating the infrastructure to collect, treat and distribute water that is more or less drinkable to every faucet in developed countries. Drinking water that is free of pathogens now seems to us the minimum that is required from water systems, unless we are ready to accept a resurgence of cholera epidemics — like in Mayotte, France, where new strains have been identified, due to lack of processing and security.

Still, rectifying problems in an architecture that has been so poorly thought out for almost a century is not an easy thing, and the cost can seem terrifying. But only on the face of it.

The report « Air Safety to Combat Global Catastrophic Biorisk” by the American organization 1Day Sooner, evaluated the cost to the United States of getting to the level recommended by the CDC, which called for more than a 50% reduction of risk of infection. For schools, this would mean an investment of $15 billion, $10 billion for hospitals and other healthcare facilities, $39 billion for offices… For all buildings open to the public, a total budget of $120 billion would be required. (This assumes optimized investments, expecting a structural reduction in costs. It could be as much as $420 billion otherwise.) That’s $360 per capita. Compare that to the cost of the pandemic in the U.S., as assessed by Johns Hopkins University, of $10 trillion. An investment that may seem at first blush excessive is actually trifling.

There remains the question of political will. And the timeframe for implementation.

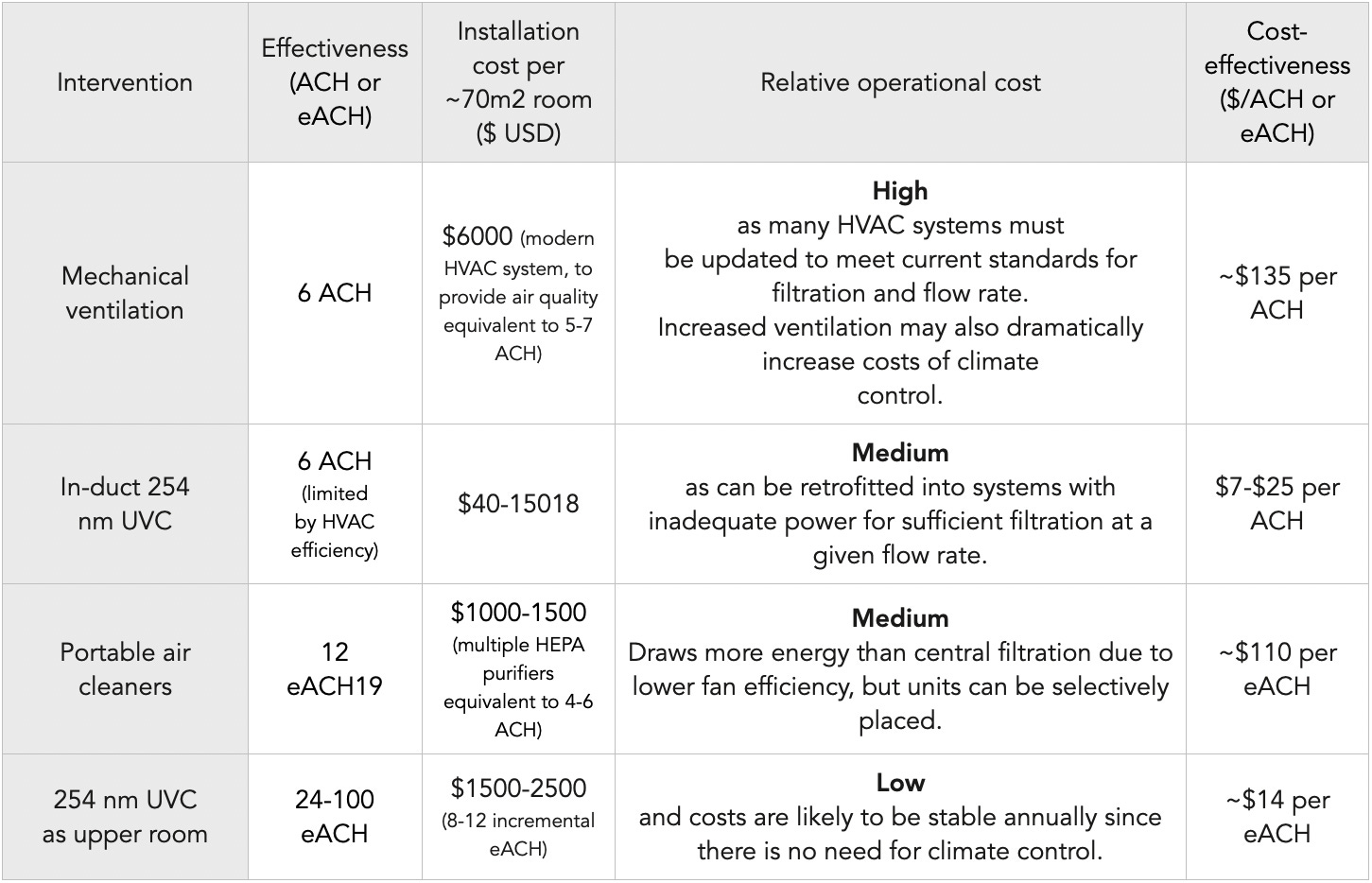

In the absence of sufficient and reliable ventilation, two other means of prevention are available:

Interior air can be filtered, in the same manner as by an FFP2 mask, but for a larger volume of air, with HEPA purifiers.

It can also be disinfected via germicidal irradiation using UV-C.

HEPA filtration3 is known and well evaluated. This involves fitting a ventilator with a certified high-efficiency filter (High-Efficiency Particulate Air). There are many such devices on the market, including some with do-it-yourself assembly. In order to protect against viruses, it is necessary to use a grade H13 or higher. Drawbacks include the noise of the ventilator, which varies according to the speed (and thus the performance) of filtration, the need for regular maintenance, the cost of replacement filters. In addition, the efficacy is very dependent on where the unit is placed, the number of people present and what they are doing.

UVGI4 is a principle of disinfection of the air by irradiation with UV-C, which has germicidal properties. This is something which has been used for nearly a century in lamps placed on the ceiling (referred to as “Upper Room”): Exhaled air, which is naturally warmer, rises, aided by ventilation if necessary, where it is quickly irradiated and disinfected, before continuing to circulate in the room. One has to be careful with the placement on the ceiling since there is a risk when the skin or eyes are exposed to its wavelengths of 254 nm. However, a more recent technology, FAR UV-C, uses a wavelength of 222 nm, which allows for UV-C radiation which can be safely directed at people.

HEPA filtration and UVGI disinfection don’t completely correct for a lack of ventilation or elevated levels of CO2, but they reliably eliminate some or all of the pathogens present in the air. They also have the advantage of not necessitating temperature corrections since there is no significant renewal of ambient air.

In the end, the low cost and ease of installation, as well as low maintenance expense, make UVGI very attractive compared with a redesign of a building’s existing ventilation systems. If the UV-C solution is chosen, the unit cost of eACH (equivalent Air Changes per Hour, equivalent to a complete renewal of air in one hour) is ten times less than for mechanical ventilation. At an investment of between $12 billion and $40 billion to protect the entire population of the U.S., and between 3 and 9 billion euros in France, these sums seem more than reasonable, given the public health benefits we can expect.

These prevention proposals are put forward, but for the moment they are just proposals, and we’re left with the indoor air we breathe. More precisely, the air they let us breathe, without guarantee or warnings of potential risks when steps are not taken to clean it.

Imagine we were still drinking untreated, unpurified tap water, unmeasured and unmonitored, without guarantee, and not held to any standard. Imagine there’s nothing you can do but continuously swallow air that may contain pathogens that are dangerous to one degree or another, that can affect your short-, medium- or long-term health, unchecked, with no one taking responsibility for the consequences that may flow from it. Well, this is the very real situation of what we are actually breathing in closed, shared spaces.

Social brutality is one of the consequences of unsuitable architecture in the context of a respiratory epidemic, because we spend 90% of our time indoors.

Social exclusion is the consequence of the only two solutions — avoidance and masking — currently open to those who are aware that a Covid infection, or one more Covid infection, could result in serious damage to their health. Personal solutions are the ultimate paradox when shared indoor air is certainly one of the most communal things in the world. We have been forcing those labeled “vulnerable” to get by as best they can. How can we best exercise our civic duties, our social life, interactions with friends, employers, co-workers, doctors, shopkeepers, government workers when they take place in spaces that may pose a threat to our long-term health? Why do the people who are aware of unaddressed, unanticipated risks have to self-exclude from these places, if and when they can? What is the impact of that, what rights are they sacrificing, what opportunities escape them?

Since Covid-19 and respiratory infections are closed-building epidemics, you may try to avoid these buildings, and live outdoors — except for your home, where some kind of air management may be more easily attainable.

The idea of living outdoors sounds preposterous these days, but that’s because contemporary architecture no longer provides for outdoor life — aside from certain leisure activities, of course. Certainly not work activity. Or healthcare. Or training. In a word, nothing. This conference could have taken place in the town square or in the park next door, and it wouldn’t have been any more uncomfortable than an overheated room. There are technical and cultural reasons for this, but they don’t all apply all the time. The rationale is largely based on being too lazy to envisage or organize something different, and in a blind confidence in and reflexive dependence on closed spaces. I bring this up to emphasize that outdoor social activities are lost in a blind spot of architecture, and that this is a driving force of the epidemic.

I would have hoped that this concept would not have been completely forgotten.

At present, the limitations imposed by avoidance are gigantic. To disappear from interior spaces, therefore from the places that make up the social hub, has plenty of negative consequences. You withdraw from society. With some exceptions, it’s a solution most had to put up with by constraints. Little by little, one’s presence in the world shrinks. First to go is the low-hanging fruit, the least discommoding, then gradually one starts avoiding occasions in closed spaces, then saying no to weekends or evenings out with friends, giving up on job interviews, putting off care judged nonessential. Up to the most difficult, and the most compulsory: showing up at work.

Another personal solution is to wear a mask. In fact, this is the only solution for the “vulnerable” which is smiled upon by the powers-that-be in this country (and they don’t make it clear that it should be a respirator, to filter out aerosols, and not a surgical mask). But wearing a mask in public has become, for the tiny minority that still wears them, a stigmatization with real psychological impact and negative daily consequences. Seeing you in your FFP2, people will wonder if you’re sick, paranoid, distraught, or all three. In any case, you will be considered fragile and unreliable. And probably a pain in the ass who brings back bad memories. How many more people would protect themselves and those around them if masks did not lead to stigma and mistrust?

And then there’s the great majority who don’t have a choice in the matter, who are unaware or don’t care about the risks. As a reminder, 90% of our life, takes place indoors, in an architecture that is ill-adapted to health.

But not all architecture and living conditions are created equal; not everybody can work at United Nations headquarters.

In 1900, a health education poster illustrated good and bad practices. Two conclusions leap to the eyes:

Good practices come down to one word: VENTILATE. Air out cribs and homes, engage in outdoor activities. Bad practices mean closed spaces, dwellings without air, a confined life.

Good practices were linked to being well-heeled; bad practices carried the stigma of poverty.

The level of risk from unsanitary conditions was linked to architecture, living conditions and social determinism.

« In the late 18th century, this correlation was statistically certain. Epidemics always hit the tenants of crowded, impoverished urban districts harder than the inhabitants of airier, wealthier neighborhoods. Patients in large urban hospitals suffered cross-infections and secondary infections far more frequently than patients in rural or small-town hospitals. It was common knowledge that if windowless rooms didn’t directly breed disease, they bred the conditions that led to disease. »5

Our living conditions have nothing in common with the towns or countryside of 1900. Failure to consider the inevitable side effects that accompanied progress, we created a trap that keeps closing in on us: because it cannot guarantee healthy air, the architecture that gives us shelter has once more become a threat. And like an echo back to the social determinism of the 19th century, it’s the disadvantaged who are most exposed because of higher density, lack of alternatives and few or non-existent options for avoidance because of deficient (or non-existent) ventilation and air renewal equipment. A classroom in the impoverished area of Seine-Saint-Denis would probably measure 3,000 ppm of CO2, more than in any high-rise office in La Défense. And we’re much more likely to find UV-C disinfection in a high-end clinic than at a public hospital. We already knew, of course, that income level was the key to the places to which we do or do not have access.

The example of the augmented ventilation installed as a precaution at the seat of the United Nations in May 2020 at the same time the WHO said – falsely – that Covid was not airborne, should have alerted us.

Different levels of wealth affect the conditions inside buildings where one spends one’s time. This means that the impact and frequency of Covid infections will not be the same for everyone.

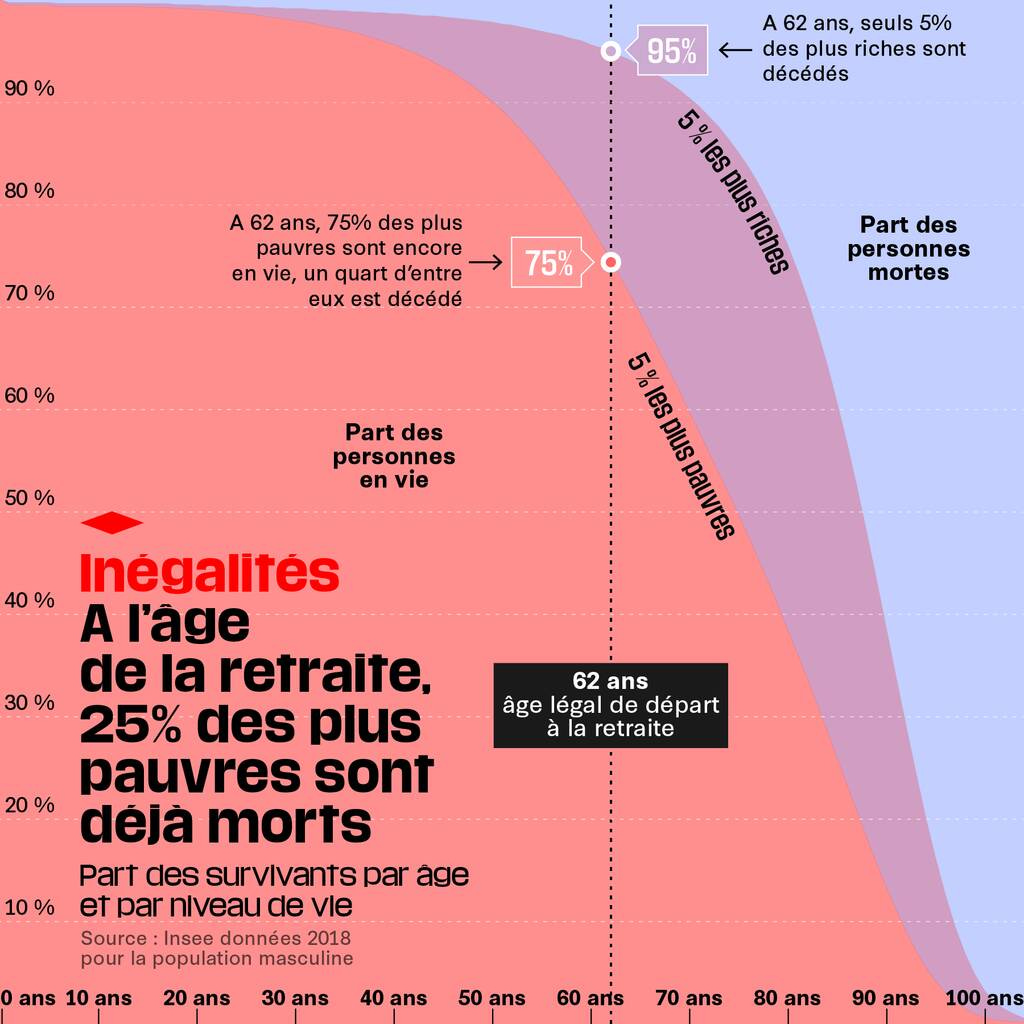

The following graph shows a familiar story. It shows that premature aging is particularly prevalent among the poor.

The Covid pandemic continues, as do other, more seasonal, infections that are spread through respiratory transmission. It reminds us that the air we breathe in the buildings in which we spend our time is an aggravating factor of inequality and contributes to widening the gap between these curves. There’s a reason why the social classes that drive public health policy, or those who promote ideologies of mass infection based on an imagined immunity — often the same people — are among those who have access to the best living conditions and the best architecture.

Among the three coauthors is Jay Bhattacharya, whom Donald Trump named in January 2025 to head the NIH, the world’s leading medical research institute. In March, the U.S. government announced the defunding of national health institutions - HHS, CDC and NIH - for everything related to Covid and Long Covid.

According to the urbanist Paul Virilio, “Every invention creates its induced catastrophe. Invent the airplane, and you invent the crash. Invent the ship, and you invent the shipwreck. We can't just simply censor accidents. […] As progress is beyond measure, it invents catastrophes beyond measure. But we are blind. We don’t think about the fatal consequences of our actions.” He says we should try to anticipate the unexpected as progress marches on. For him, the two cannot be dissociated from each other.

Publications HEPA filtration :

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034124003848

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195670122003127

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9990385/

https://bcmj.org/premise/hepa-filtration-reduces-transmission-sars-cov-2-and-prevents-nosocomial-infection-call

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/75/1/e97/6414657

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021850225000643

Report from Canada Health on the efficacy and safety of UV-C disinfection (Upper Room 254 nm and Far UV-C 222 nm) with respect to Covid-19:

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse/summaries-recent-evidence/ultraviolet-germicidal-irradiation-technologies-use-against-sars-cov-2.html